When I heard about the assassination of Qassim Suleimani, the head of Iran’s Quds Force, by an American military missile strike at the Baghdad airport on January 2, I immediately thought of the repercussions. They are likely to be global, perhaps provoking another war. American military and government installations around the world may become targets.

The balance of power in the Middle East will be affected, and hardliners in Tehran will be strengthened. They have always been suspicious of America’s intentions, even during the short-lived nuclear peace agreement, and now they have new reason to build up Iran’s nuclear armaments.

But my immediate thoughts were not about this broader spectrum of dire consequences from a decision that appears to have been made quickly without extensive consultation by a President notorious for disastrous spur-of-the-moment foreign policy decisions. Rather, I thought about the affect within Iraq, where Suleimani was killed.

I have visited Iraq many times since the US invasion in 2003, and have developed friendships with colleagues especially in the Kurdistan region in the north. I fear that the rising US-Iran tensions will have an adverse effect on Iraq’s minorities—particularly the secularists, the Sunnis and the Kurds.

When I first went to Baghdad in 2004, shortly after the fall of Saddam Hussein, I talked with many academics, journalists and politicians who were hopeful about the rise of a secular democracy and new political parties organized around the interests of workers and farmers. Instead, politics in Iraq has devolved into ethnic and religious sectarian movements.

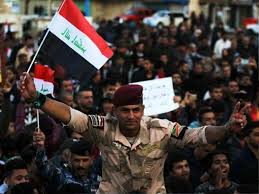

The spirit of secular democracy has persisted, however, and has been expressed most recently in the huge public rallies supported especially by young people protesting political corruption and the insidious ties to Iran. Now that Iran is under attack by the US, and the US has been using Iraqi territory as the base for which those attacks have been made, these protests have been drowned out in clamor for a martial patriotism to defend the sovereignty of Iraq. The power of the Iran-related Shi’a political parties in Iraq has been solidified.

The strengthening of Shi’a political groups is bad news for the two major ethnic minorities in Iraq, the Sunni Arabs in the Western region of the country and the Sunni Kurds in the north. My friends in the Kurdistan region have admired Americans and enjoyed the support of the United States over the years, beginning with an American-enforced no-fly zone over the Kurdistan region after the Gulf War. The Arabs in the rest of Iraq treated them as second-class citizens, and Kurds had few political allies in the region.

Though the ethnic community of Kurds comprise some 40 million people in eastern Turkey and the northern regions of Iran, Iraq, and Syria, they do not have their own nation. Moreover, their separatist aspirations are suspect in each of these four countries in which they have large populations. The United States supported them against Saddam, and then found in them useful allies in the fight against the Islamic State. Kurdish forces in Syria and Iraq were crucial in ending the territorial control of the Islamic State in 2018.

The Kurds assumed that the US would show its gratitude by giving them continued support, but alas the capricious decision by US President Trump to withdraw protective American troops from Syria in 2019 left them vulnerable to Turkish incursions into the Kurdish areas of Syria. The most recent anti-American mood in Iraq following the assassination of Suleimani will make the Kurdish pro-American stand even less acceptable to Baghdad. It also makes the Iraqi Kurds feel more vulnerable, since the US is increasingly not in a position to come to their aid, even if it was disposed to do so.

The Sunni Arabs in Iraq also will feel abandoned in the pro-Iranian mood following the Suleimani assassination. When I talked with Sunnis in refugee camps who have fled ISIS-controlled territory in western Iraq and Syria, many of them said they feared Shi’a control more than the harsh terrorist regime of the Islamic State.

The overwhelming number of ordinary Sunnis who supported ISIS during its heyday did so because they felt excluded from the Shi’a- dominated political life of the country, and marginalized when it came to receiving government jobs and benefits. Participation in the Islamic State was a form of Sunni empowerment.

When the ISIS regime was defeated in the main Sunni Arab cities—Ramadi, Fallujah, and Mosul—what was left behind were scenes of utter destruction. Very little government funding or other efforts have been made to restore the infrastructure and help in the rebuilding of these cities. Many of the residents languish in the enormous refugee camps erected in the Kurdistan countryside.

The Sunni dissatisfaction and fear of Shi’a militia has bolstered ISIS and led to an underground resurgence of the movement. The increased power of Shi’a politics and the unleashing of militant Shi’a groups such as the Sadr Brigade will only harden the Sunni antipathy towards Shi’a control and bolster the rejuvenation of the ISIS movement.

On the evening after the assassination of Suleimani, pronouncements from the White House and Pentagon focused on this one man, who was admittedly a mastermind of many treacherous operations throughout the Middle East. The implication was that in destroying Suleimani, a measure of peace would come to the region. Alas, however, the death of this one man may lead to a spiral of consequences, affecting most immediately Iraq’s minorities, the secularists, Sunnis and Kurds.