The role of religion in the new Cold War between democracy and authoritarianism. An excerpt from an upcoming article in Oxford University’s St. Antony’s International Review.

The recent political shifts on a global scale have led many observers to conclude that we are on the verge of a new Cold War. But it is not clear what the opposing sides are, nor how they are constituted. Some observers point to the rising tension between the United States and China as a new point of contestation. It is a conflict, to be sure, but it is essentially a bipolar one. To be a new Cold War one would expect it to have a global reach, and present opposing ideological basis for organizing public life.

What is emerging at this point in the third decade of the 21st century as an opposition on a global scale is the conflict between democracy and autocracy. Like the old Cold War, the states on either side do not always agree with one another. The Soviet Union and China were uneasy partners in the Communist bloc. But they leaned on each other for support in times when they had to face their ideological opponents—democratic capitalism in the case of the Communist partners. In an eerie way, global politics seems to be lining up in a similar kind of mass dichotomy between two uneasy though warring camps.

The rise of authoritarian nationalism in recent years has been remarkable. The increasing control of Xi in China, the ascension of Putin as a Russian dictator, the emergence of Erdogan and al-Sisi as the strong men of Turkey and Egypt; the rigid regimes of South Korea, Iran and Saudi Arabia; the dominance of Modi in India; and the authoritarian tendencies of the Trump administration in the United States provide a counterweight to what was once a near-global acceptance of democracy. Though hounded by autocratic right wing parties, the democratic spirit still thrives in Europe, elsewhere in the Americas, and in much of Africa and Southeast Asia. The two sides are by no means united except in their persistence in the differing tracks on which they have traveled. And the confrontation is nearly global.

The stance of Trump in disdaining traditional European democracies in favor of the autocracies of Russia, Hungary, Turkey and even North Korea is an example of these new alliances. When Russia reached out to Iran and North Korea for assistance in its invasion of Ukraine, it demonstrated the new alliances.

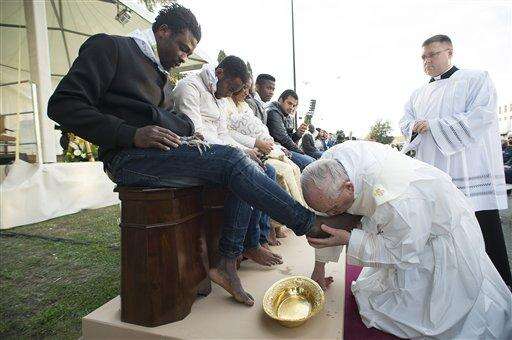

What is particularly interesting to me, as someone who has observed the global connections between religion and politics over my now long career, is the role of religion in this new Cold War. Many of the new autocracies are openly built on religious nationalism. This is a development that has been several decades in the making, and it is striking to see it emerge as a dominant force in the present confrontation. In Russia, Putin leans on the Russian Orthodox church and its Patriarch Kirill for support. The regime of Saudi Arabia has built its power on the religious network of Wahhabi Islam, just as Iran’s theocracy is based on Shi’a institutions. In India, Modi wears his Hindu identity strongly, and his political party is based on an old Hindu nationalist movement that dates back to the beginning of India’s Independence movement. The support of Evangelical Protestant Christians in the United States has given Trump his strongest base. Religion is part of the emerging autocracies of the new Cold War.

At one time I thought that it might be one side of a cold war, the conflict between religious and secular nationalism. Thirty years ago I published a book with the title, The New Cold War? Religious Nationalism Confronts the Secular State.[i]At the time it seemed a startling proposition that religion could play a role in a new kind of anti-secular authoritarian politics. Religion was, however, a significant part of the power politics of the Middle East, and religious nationalism was emerging as the rival to secular democracy in other parts of the world as well.

Fifteen years later the book was completely rewritten and reissued with the title Global Rebellion: Religious Challenges to the Secular State. The reason for the change in title was that the revised book covered a wide range of non-state movements, some of them transnational such as al Qaeda. The role of religion in these oppositional politics was a potent force, but it was scattered among a broad range of movements. At the time, it seemed less like a global confrontation in the way that a Cold War would suggest, and more like a global rebellion.

Today’s situation provides yet another context for thinking about the role of religion in global conflict. My original title, “the new Cold War,” again appears to be prescient. It is not, however, the way that I originally thought, or as I later revised my thinking. It is not that religious nationalism itself is one side of the confrontation or that it foments rebellions, but that it plays a significant role in buttressing the power and providing the mobilizing force of dictatorial regimes in the emerging global conflict of the present: the new Cold War between autocracy and democracy.

Hence, thirty years after I first published The New Cold War? the theme has returned. Religion provides the potency to shore up right-wing power, anti-immigrant hate and economic isolationism, and for that reason it is part of the equation in the current dichotomy between democracy and authoritarianism. For strongman regimes in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Hungary, Russia, India, and now the United States, religion is often a way to connect the masses to a powerful state.

[i] Mark Juergensmeyer, The New Cold War? Religious Nationalism Confronts the Secular State (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.