We think we know all about Hamas. Our understanding of the movement is is shaped largely by the horrific images of sadistic terrorists ravaging a peaceful rock concert and settlements in Southern Israel when they breached the border and conducted a savage rampage on October 7. Since then this view of Hamas as unspeakable evil has been enhanced by the public pronouncements of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the Israeli press.

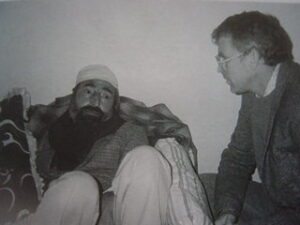

My own perception is somewhat more nuanced, based on my interviews with Hamas leaders, including the founder, Sheik Ahmed Yassin, some years ago when I was in Gaza. My information has been buttressed by more recent communications with Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank.

What I know about Hamas complicates our picture of it, and raises several basic questions.

- Is Hamas is a united organization?

When I talked with leaders of Hamas some years ago I was struck by how disorganized the movement appeared to be, and how fluid were many of the loyalties. I was scheduled to meet with one high-ranking leader of Hamas, but by the time I met with him he had already jumped ship and become a supporter of its rival, the Palestinian Authority. Other leaders acknowledged that there was internal dissention and controversy, especially over some of the Hamas tactics at the time, including the use of suicide bombers.

Though the October 7 attack was extremely well planned, likely years in the making, and involved a complicated organizational support structure, it is also likely that many Hamas officials and supporters were unaware of what was going on. It is well known that Israeli intelligence has spies within the Hamas organization, though in this case they were not well enough placed to know about the secret plans of October 7. Hamas as a political organization includes hundreds of government employees who were probably not only unaware of the attack plans but also likely to have been opposed to them, knowing the reign of terror that this would unleash from Israel’s military defenses.

At the other extreme of the political spectrum were rogue groups of militants who thought that Hamas was too moderate, including members of the Islamic Jihad movement. Many of these non-Hamas militants seized on the opportunity of October 7 to join the attack and carry out their vicious wrath on Israelis unabated. Some of them were little more than sociopaths and street thugs, with no official links to Hamas. The planned attacks of Hamas were savage enough. But these fringe elements likely made a horrible situation even worse. Alas some of these rogue elements also took hostages, making the negotiations with Hamas for their release even more difficult.

If one could roll back to the calendar to the days immediately after October 7, these divisions within Hamas could have been exploited by Israel. It is not impossible to imagine a scenario where Israel could have worked with disaffected Hamas leaders to create an alternative Hamas council to run the Gaza territory. Stoking an internal battle within Hamas might have been as effective in countering the militant Hamas leadership as military engagement, though it would have been a difficult maneuver to achieve. It also would not have had the effect of providing a sense of retaliation to a traumatized public yearning for strong action in response to the October 7 massacre. Still, the military invasion could have been conducted in such a way as to protect and curry favor with the opposition within Hamas’ own ranks.

- Do all Palestinians in Gaza support Hamas?

This brings up another question, regarding the degree of popular support Hamas had among the wider population in Gaza. Though the Israeli military operation treated all of Gaza residents as terrorist supporters, it seems unlikely that was the case.

In my recent conversations with people from Gaza, they claimed that a sizable percentage, perhaps the majority, despised the Hamas organization. It’s difficult to know the exact number, not only because of Hamas intimidation but also because there have been no elections in twelve years. It is true that the movement came to political power in Gaza through free elections in 2006, but it’s likely that this was due to disaffection with the ruling Palestinian Authority at the time as much as it was to an attraction for Hamas.

After years of Hamas’ mismanagement, authoritarian control and economic stagnation, many if not most of the Gaza population has been yearning for an alternative. Though Hamas did not allow opinion polls within Gaza, on the Palestinian West Bank the support for Hamas prior to October 7 was only 12%, though after the Israeli military invasion in Gaza the percentage has raised dramatically.

The prior disaffection with Hamas could have been a useful tool for Israel in its attempts to crush the militant leadership after the October 7 massacre. In my recent book on how religious terrorist movements end, When God Stops Fighting, I report on the inside perspective of three movements, including ISIS, that have been terminated. In each case, old militants in the movements told me that what destroyed the movements was the break-down of support from the general populations they tried to control.

In the Gaza situation, this disaffection could have been harnessed by Israel. It is likely that ordinary citizens of the region were disgusted with the savagery of the October 7 massacre and would have turned against those leaders of Hamas involved in it. Israel might have been able to collaborate with them to help to locate the Hamas bases and fighters. The Awakening movement engineered by US General David Petraeus in Iraq was able to do just that in turning local Sunni Arab leaders against a precursor to ISIS, al Qaeda in Iraq, and essentially defeating its power in the Anbar region of the country.

Though almost all Palestinians despise the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory they would not all have endorsed the cruelty of October 7, and many would likely have turned against the movement, especially if offered the promise of a long-range solution to Palestinian autonomy in the future.

Instead, the massive destruction of Gaza buildings in the weeks since October 7 and the tragic loss of life—overwhelmingly women and children–has likely turned even moderate Hamas-hating Gaza residents into bitter enemies of Israel and grudging supporters of Hamas.

- Do all Hamas supporters want to completely destroy Israel?

One of the most common truths repeated about Hamas supporters is that they are dedicated to the total destruction of Israel and all Israelis. Certainly some are. Moreover the goal of Israel’s eradication is in the Hamas charter, which has never been repealed.

But when I talked with Dr Abdul Aziz Rantisi, one of the founders of Hamas and its political head, he repeatedly told me that he had nothing against Jews as a people or Judaism as a religion. He said that if the situation was reversed, and Palestinians were in charge of the whole Israel-Palestinian region, Jews would be welcome to stay and claim the territory as their homeland as long as they did not control it. Moreover, Rantisi talked about collaboration with Israel in a way that implied a tacit acceptance of the existence of the state of Israel.

Former President Jimmy Carter reported the same thing. He was told by Hamas leaders that they could live with the state of Israel limited to the 1967 borders if they allowed Palestinians to have their own independent state.

But as I said, the charter of Hamas calls for the destruction of Israel, and this clause has never been revoked. Doing so would likely have set off a firestorm of controversy within the Hamas movement, where many members do indeed yearn for the total destruction of Israel. The leadership of the movement would like to avoid that kind of internal turmoil. Hence some have quietly interpreted the strident language of the charter in a way that is more realistic and opportunistic.

When Hamas organized as a political party twelve years ago and ran candidates for offices in Gaza and the West Bank, many members of the movement opposed this move. They thought that recognition of the political structures of Gaza and the West Bank was tacit acceptance of the state of Israel and its limitation of Palestinian control. Nonetheless, the decision at the time was to work within the existing political framework.

The October 7 attack clearly showed, however, that the militant wing of the Hamas movement would not accept the status quo and wanted to literally blow up the walls that kept it imprisoned. Some of them wanted to kill and maim and torture as many Israelis as they could find. Whether the rest of the Hamas movement and the vast majority of Palestinians in Gaza supported this tactic is questionable.

Whether these dissenters could have been marshalled in opposition to Hamas and as a base of a more moderate leadership in the territory is unknown.

The reality at present is far different, however. The Israeli military blitzkrieg has created a population more bitterly opposed to the oppression from Israeli than from Hamas. And the future is far from certain.