A new paperback edition of God at War with a new Preface, just out. Oxford University Press is selling it for just 20 bucks. Or you can listen to the audio version of God at War. This is the Preface for the new edition:

When the head of the Russian Orthodox Church and a staunch ally of Vladimir Putin, Patriarch Kiril, proclaimed in his Easter Sunday sermon on March 5, 2022 that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was not just an ordinary conflict but one with “metaphysical significance,” he was saying something fundamental about the role of religion in war. God was not just on Russia’s side. The war itself was of transcendent proportions.

A similar notion appears to have been in the mind of Yahyah Sinwar, the leader of Hamas who gave the order for the attack on Israel on October 6, 2023. Sinwar is said to have compared himself with Saladin, the great warrior in Islamic history who liberated Jerusalem from Crusaders in 1187 CE, thereby placing himself in the pantheon of heroes in Islamic history.

A religious mission is also in the thinking of some right-wing members of Israel’s cabinet as they pursue the war against Hamas in Gaza. Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israel’s Minister of National Security and leader of the Jewish Power Party, subscribes to the idea of Eretz Israel, the God-given right of Israel to all of the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. He has encouraged Palestinians fleeing the conflict to permanently leave Gaza and allow Jewish settlements to return.

In both the Ukraine and Gaza wars, religion has played a role, as it has in many other conflict situations around the world. But what kind of role? We know that often religious figures are brought in to bless soldiers before battle and that religious literature is full of images of warfare. It is clear that in these ways war needs God and religion needs war. But there is also a third option, when the idea of God and the idea of warfare are intertwined in one apocalyptic notion of cosmic war.

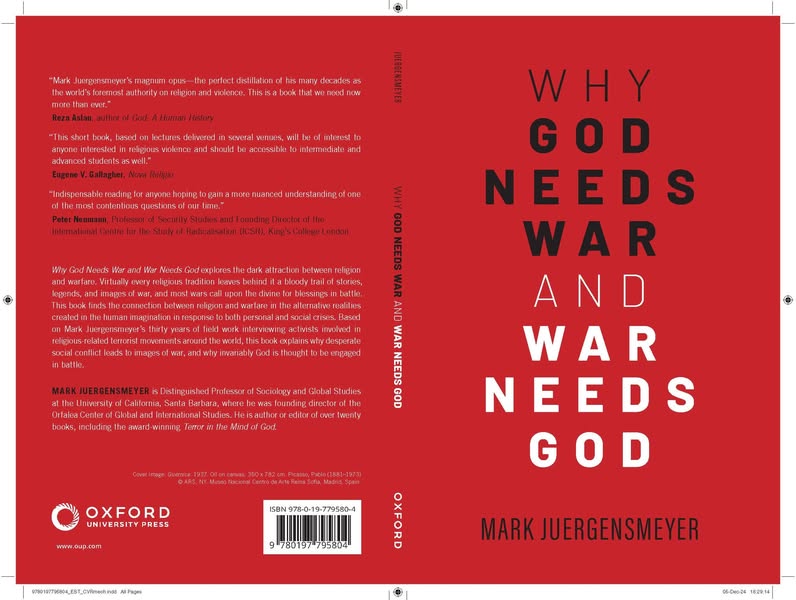

It is these ways of thinking about the relationship between religion and war that will be explored in this book. It will attempt to make sense of this dark relationship between violence and divinity and probe into the essential nature of both that makes them compatible with one another. What is it about the very essence of the idea of war that cries out for religious verification, and what is it about the character of the religious imagination that war is so easily assimilated into its world views?

My thinking about this has been seasoned over many years of studying religious-related violence in the rise of militant movements globally in virtually ever major religious tradition. I have drawn upon my field work and conversations with activists in Iraq, Israel, Egypt, India, Japan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Philippines, the United States and elsewhere to understand the phenomena of religion and violence from the perspective of militants engaged in lethal struggles.

I sometimes speak of these phenomena as incidents of religious violence, but I do not mean by that that religion causes violence, any more than the phrase “religious art” or “religious music” means that religion causes art or music. Rather, I mean that religion is related to these things in some way. Just how they are related is what I want to explore.

In writing this book I was engaged in a five-year series of case studies of three militant religious-related movements—ISIS in Iraq, the Khalistan movement in India’s Punjab, and the Moro movement in the Mindanao state of the Philippines. Having studied the rise of violent religious movements over many years I wanted to know how they ended. This meant understanding how they detached the religious images of transcendent warfare from the earthly struggles that could more easily be mitigated. Hence my renewed interest in what war was, and what religion had to do with it.