I received one of the first grants given by the United States Institute of Peace shortly after it was established in 1984. After a violent uprising of Sikh activists emerged in India’s Punjab state, a region in which I had lived for several years, I embarked on what would become a forty-year study of the rise of religious violence, nationalism, and terrorism around the world.

My project began with USIP support. Since the institute was brand-new it had only a suite of administrative offices rented in a downtown Washington DC office building. There was no place to house the recipients of its grants, which suited me just fine. Most of my research was held abroad anyway, initially in the Punjab, then elsewhere in South Asia and the Middle East.

The Institute of Peace was a long time in coming. It was a dream of Hawaii’s Senator Spark Matsunaga. He thought that since the US had funded the largest department of defense of any country in the world, it could invest a tiny fraction of that in a department of peace. The institute would be the first step in this goal.

The institute was basically a research center in conflict resolution. It was organized around areas of the world in which conflicts were brewing, which alas included pretty much all of the world. The research projects focused on the reasons for the conflicts, and the paths to resolving them. My project on religious violence in India and elsewhere fit perfectly in their format.

From the beginning the institute was designed to be separate from the government, to give it the independence to do research and help to negotiate peace settlements unfettered by political whims. The institute is officially an NGO (a non-government organization), not a government agency, and its charter precludes any of its staff or grantees to be employed by the government.

The funding, however, is entirely from the US government. The reason was that the founders did not want money to skew their projects, so no outside contributions were allowed. Presumably the US Congress would provide what it needed — $55 million a year in recent years – and step aside and let the USIP do its thing. Because of the funding connection, however, the US President appoints the members of the overseeing board, confirmed by the Senate.

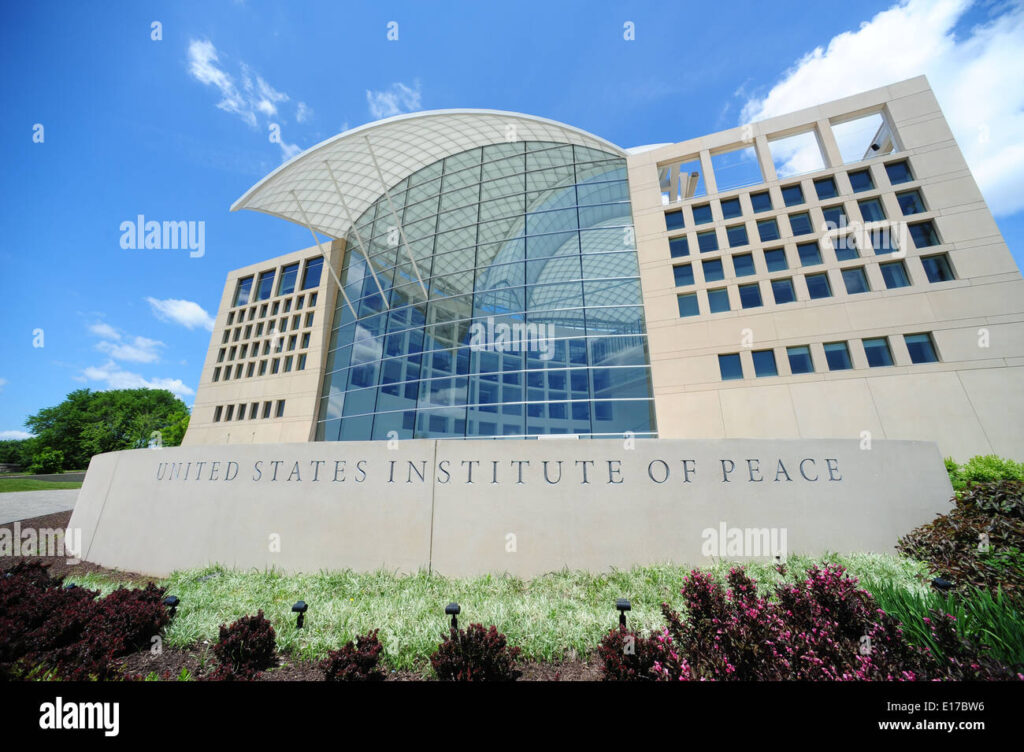

The institute had to go back to Congress to get permission to go beyond its rules and seek outside money – not for projects, but for a building to house the administrative offices and the researchers. Congress approved, the cash was raised, and in 2011 a striking new building was constructed on land provided by the US Navy. An architectural gem, it is located in Foggy Bottom next to the State Department and across the street from the Vietnam Memorial and Lincoln Memorial on the Capitol Mall. It is not a government building, since it is owned by the independent NGO of USIP.

Most of the projects funded by USIP are case specific. They included study groups focusing on critical issues in such regions as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Sudan, South Sudan, and elsewhere. The USIS has supported negotiation teams and advised government agencies on appropriate policy, including Congressional committees and the intelligence community. In 2007 a USIP team helped to broker the peace deal in Iraq that led to the withdrawal of US forces. In short, their projects are well worth the $55 million, a drop in the budget compared to defense funding.

Even so, the USIP was on Trump’s chopping block. As one worthy agency in the US government was crippled, one after another, Elon Musk’s dreaded DOGE finally found its way to USIP. Trump promptly fired the staff and the board, and the DOGE goons arrived to take over the building.

They were met at the door by USIP personnel who protested that this was a non-government agency and the building was owned by an NGO. The DOGE squad had no business being there. The DOGE commandos stepped back and then returned with a police escort. The police demanded entrance, and the front door was opened as the DOGE squad raced inside, changing the locks and demanding that everyone leave the building.

The staff of USIP immediately fired off a legal challenge, protesting that it was an independent NGO, and the building was not owned by the government. Members of the board, however, were under Presidential appointment. Trump was thus able to assert his legal right to strip the place bare, leaving only the minimum allowed by law, namely the board and its new president, a MAGA sycophant. Nothing else.

Now you have a beautiful but empty Peace building. It is perhaps a perfect symbol of this administration’s attitude towards conflict resolution.

The ideas behind the institute, however, are needed now more than ever before. Like the supposedly vanquished foes in many of history’s wars, the US Institute for Peace may one day rise again.