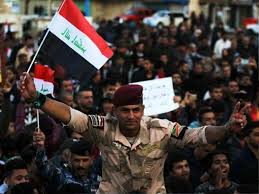

Talking with Sunni Arab Refugees from ISIS near Mosul in 2019

In March 2019, the last bit of ISIS-controlled territory at Baghouz on the Syrian-Iraqi border fell to Kurdish fighting forces and their allies. Later that year its vaunted Caliph, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, was killed in a US military assault in northeastern Syria. President Trump proudly proclaimed the end of ISIS.

Yet intelligence reports indicate that the movement is far from dead. In fact, it appears to be on the rise. In 2019, there were estimated to be 18,000 ISIS fighters remaining in guerrilla cadres. These sleeper cells and strike teams have conducted sniper attacks, ambushes, kidnappings and assassinations. They were particularly active in rural areas of the badly-policed borders between Syria and Iraq and between Iraqi Kurdistan and the rest of the country. Their targets have been government and foreign forces and anyone thought to be collaborating with them.

In 2019 the numbers of attacks increased over the year. In the first six months in Iraq alone there were almost 280 people killed in ISIS guerilla assaults, including erdUS contract security personnel. Among those killed was a Sunni Arab guard in Ramadi who went out at night to check up on his uncle’s farmland and was abducted and beheaded with a warning that a similar fate would await anyone who worked for the government.

The numbers of incidents this year are already up. The question is why? Why has ISIS returned so quickly, and why is it thriving?

The basic reason is that the conditions that encouraged so many Sunni Arabs to support ISIS have not changed. Their feelings of marginalization in Shi’a dominated Iraq and Alawite-dominated Syria have continued to make them second-class cities. Worse, some of their major cities, like Raqqa in Syria, and Mosul, Ramadi and Fallujah in Iraq, have been destroyed in the battles to end ISIS control. The Sunni Arabs who lived there often have nowhere to return.

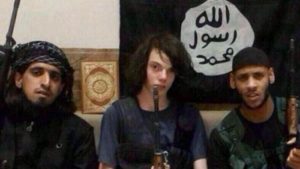

As a result hundreds of thousands are languishing in refugee camps, where tentative hope has eroded into despair. There the ISIS message of Sunni Arab empowerment falls on receptive ears, especially among young men who find little opportunities for employment or education in the camps.

In the last several months, moreover, there are four other factors that have emerged that have propelled ISIS’ revival. All of them are related to policy decisions made by the U.S. President, often with little consultation with experts and advisors, and with little assessment of the potential consequences. These factors will have a long-range effect in strengthening the revival of ISIS:

Control in Syria diminished

When President Donald Trump announced that US forces would withdraw from the Kurdish regions of Northern Syria the shock waves were felt throughout the region. He had apparently made the decision on the spur of the moment during a telephone call with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Within a day Turkey was moving its troops into the area, pushing out the Kurds who lived there, planning to create a new buffer zone to relocate Syrian refugees and deny the Kurds a homeland from which they might influence Kurdish separatists in Turkey.

Since Kurdish forces had led the opposition against ISIS in the region, this meant that Kurdish troops were no longer able to patrol the region. The Russian-backed Syrian army was not adequate to the task. Hence the ISIS cadres had almost free reign to operate again within the formerly Kurdish-controlled areas of Syria.

Prisons left unguarded

Kurdish forces had maintained the detention centers and prisons in Northern Syria where some 10,000 former ISIS fighters were incarcerated. With the need for Kurdish troops to protect their own people in the face of the Turkish army that was trying to force an ethnic cleansing if Kurds in the region, many of the detention centers were suddenly seriously understaffed after the US decision to no longer project the Kurds. Prison breaks since then have released hundreds of seasoned ISIS militants back into society.

Control in Iraq diminished

Much of the containment of ISIS in Iraq was due to policies orchestrated by Iran through the Quds Force Commander, Qasem Soleimani. It was widely suspected that he had worked hand and glove with the US military in coordinating their offensive strategy against ISIS, despite his role in supporting anti-American groups throughout the Middle East. When he was killed in January 2020 through a US military strike ordered by President Trump, whatever coordination existed between the US and Iran was severed, and the specific strategies that were directed by Soleimani no longer had his skillful leadership to guide them.

Shi’a Extremists Emboldened

Perhaps a more important and long-lasting outcome of the assassination of Soleimani is its effect in emboldening the extremist activists within the Shi’a communities of Iran and Iraq. The moderate leaders had gambled their reputations on a peace agreement with the United States brokered in the administration of President Barack Obama, and when Trump reversed the US stand and pulled out of the deal, the hardliners appeared to have won. The killing of Soleimani was the last straw in the moderate approach. What this means is that extreme Shi’a militia now have greater liberty to prey on their ethnic rivals, Sunni Arabs and Kurds, who already are marginalized in the Shi’a dominated politics of Iraq and Syria. The beneficiary of this increased ethnic polarization is ISIS, which thrives on the suffering of Sunni Arabs, providing a voice for the dispossessed.

In a curious way, then, the effect of recent US actions in the region emboldens ISIS. By alienating Sunni Arabs, strengthening Iranian and Iraqi Shi’a hardliners, and withdrawing support from ISIS primary enemy, the Kurdish forces of Iraq and Syria, the US under President Trump has given ISIS a new lease on life.

US Intelligence figures of the number of ISIS related incidents in 2019 are cited in Eric Schmitt, Alissa Rubin, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “ISIS is Regaining Strength in Iraq and Syria,” The New York Times, August 19, 2019.