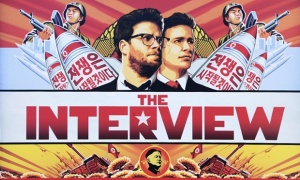

In watching the movie, “The Interview,” I found myself comparing the fictional sets of North Korea with what I saw when I was there some years ago in the early 1990s when I was a guest of Kim Il Sung University (yes, there is a Kim Il Sung University). I was there for ten days, helping to negotiate collaborative projects with the University of Hawai’i as dean of their School of Hawai’ian, Asian and Pacific Studies.

North Korea’s capital city, Pyongyang, appeared much like the movie sets. I arrived at the airport terminal, which looked exactly as it did in the movie, and was whisked off on a beautiful multiple lane freeway to the heart of the city. The film accurately portrayed its skyscrapers, including a 105 story pyramid-shaped hotel, towering in the background.

The only odd thing about my initial impression was that the fancy freeway from the airport was almost empty. It seemed more a showcase for a modern highway than a functional one. The same can be said for the hotels, which looked terrific but were scarcely occupied.

We stayed in the twin-towered Koryo Hotel aimed, apparently, at businessmen since there was a glossy brochure on the coffee table, in English, trumpeting the export items that North Korea was prepared to offer. The month we were there they were featuring Russian style tractors and rabbit fur. I imagined a lovely combination of the two. The companion tower outside my window was completely dark at night, and there were only about twenty people at the mandatory breakfast in the morning. Not that many people wanted to vacation in Pyongyang, I guess.

Even so, we appeared to be in the glitzy area of Pyongyang, since outside the hotel was a block-long line of nightclubs and cafes, brightly lit on the outside. Since the streets were curiously empty, I was interested to know whether there were any customers inside, so I ventured downstairs and out into the sparkling street. Suddenly the lights went off—all of them, for all of the nightclubs and cafes—at the same time. Like one of the characters in the movie who discovered that a well-stocked vegetable store was a false front with fake food, I found that these cheerful bistros were only facades and there were, in fact, no cafes and nightclubs at all.

We had a similar experience in checking out the local stores. One was indeed well stocked with televisions and foreign motorcycles and myriad other modern amenities. But it was restricted to people who could buy things with foreign exchange, particularly Koreans from Japan whom the North Koreans were trying to lure back to the country. The stores that sold goods for Pyongyang’s residents were almost bare. They would sell things episodically, depending on what was available. When were there, it was plastic buckets and rice.

Yet there was much grandeur in Pyongyang: sweeping plazas, massive monuments, imposing government offices, and everywhere statues of the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung, who was still alive when I was there. Other statues portrayed the Beloved Comrade, Kim Jung Il. The poses were predictable: figures standing in the wind, pointing wisely towards the distance; sitting wisely like Abraham Lincoln in a throne-like chair; or standing with hands akimbo looking triumphantly—and wisely—at the less fortunate world. These were the large public statues. Little busts were legion, as where the ubiquitous red and gold pins with images of the Great Leader.

The North Koreans were proud of this over-built monument-packed city, and justly so. Frequently they would show us pictures of what Pyongyang looked like at the end of the Korean War, just a rubble-strewn desert of total disaster. It was the result, we were told knowingly, of the aggressive American military that had ruthlessly attacked the country. Only the brave defensive struggles of the North Korean soldiers allowed it to survive. Our hosts seemed unaware of the historical accounts that describe North Korea as the initiator of the war, and the role of the Chinese in helping it seize South Korea and prompting American troops to defend it. Their account placed all the blame on the bloodthirsty Americans and you could feel their paranoid fear about the likelihood that the US would attack again. Perhaps soon.

They credited their resilience to Juche thought, the ideas of Kim Il Sung. We visited an imposing tower in a pleasant setting beside the main river commemorating these ideas, an ideology of self reliance that was revered even more greatly than communism. They implicitly blamed both the Chinese and Russians for not helping them rebuild after the Korean War, and having to do it by themselves. So modern Pyongyang was a showcase of North Korean grit and pride.

Students in North Korean Universities, however, knew that the future lay in the wider world. They were eager to become connected with the international economy. Computer science was a popular topic, and though the computers in their classrooms appeared outmoded they were everywhere. English was the preferred foreign language, even more popular than Chinese, Russian, or Japanese.

Like the movie version of North Koreans, my hosts tried to repair their image of being a poverty-stricken dictatorship, and show that they lived well and were able to tolerate diversity. They were particularly proud of neighborhood health clinics that also included gyms and work-out facilities and beauty parlors. I don’t know how common these were, but the ones we saw were indeed serviceable and well used.

And there was a certain amount of religious freedom. I was eager to see if Christianity existed in North Korea, so on Saturday I announced that I would like to go to church the next day. “Which kind,” my hosts asked, “Catholic or Protestant?” Thinking quickly, I told them “both,” explaining that since I was such a devout Christian I had to go to both kinds of services. So the next day they took me to both, and there were indeed churches that looked like churches, pews full to the exact number of spaces available in the buildings, and everyone singing hymns without looking at the books, and kneeling and praying at appropriate times. In other words, it seemed unlikely the whole thing could have been entirely staged for my benefit, especially since I gave very little advanced notice. But how many churches there were I have no way of knowing.

Venturing out in the countryside was a relief from the artificial, monumental Pyongyang. We went on a full-day outing to the Kumgang mountains, the dramatic sugarloaf looking peaks near the South Korean border. Along the way we stopped at a small town that seemed reasonably well off and bathed in the hot spring pools that were the local attraction. We also passed by a mammoth dike built to keep out the ocean and reclaim land for farming, and a nuclear power plant.

We wanted to visit a farm, so our hosts took us to one that seemed to be on the visiting foreigners circuit. It seemed suspiciously prosperous. The whole family was inside the living room, watching programs on a shiny new television. We were impressed, until I went around the back in search of a bathroom and saw the cardboard box in which the television had arrived, most likely that morning, and to which it likely would soon return.

So the North Korea of my memory was much like the one portrayed in the movie, The Interview. The cityscape was much the same, and so was the paranoia and mindless devotion to the Great Leader. It seemed to me as if I had been visiting the precincts of some enormous religious cult. And in a way I was.

The day before I left, I went to a small shop in the lobby of the hotel, and amassed a large collection of Kim Il Sung buttons and pictures and statues to take home as souvenirs. But initially the North Korean lady at the cash register refused to let me purchase them.

“You don’t really believe in this,” she said, “you just want to make fun of us.”

“No,” I protested, saying that I had great respect for the North Korean people and their leadership. All I wanted to do was to take back home some symbols of their devotion to let my friends in America so they could experience what I had discovered about North Korean sensibilities.

She looked at me suspiciously and eventually relented and let me buy the trinkets. But, although I didn’t quite lie to her, it is also true that her initial reaction was correct.