The hideous images of orange-clad Westerners kneeling beside black-draped executioners that have been broadcast from ISIS-controlled Iraq recently are eerie reminders of similar scenes just ten years ago. At that time the terrorists were agents of Al Qaeda in Iraq, the predecessor of ISIS.

Why did they use such extreme measures then, and why do they now, and what is the difference between the two? The answers to these questions tell us much about how terrorism works, and how it plays a role in the present Sunni politics of Iraq.

As I argued in my book, Terror in the Mind of God, most acts of terror are instances of performance violence. They are dramatic events meant to shock, and to lure the viewer into the perpetrators’ worldviews. These are performances intended for very specific audiences, including the worldwide audience on television and the Internet.

Take 9/11, for example. Anyone seeing this on television –and that includes most of the developed world—would see an image of war. For the moments that they were stunned by such an image they would be drawn into the worldview of jihadi activists, a view of the world engaged in a great cosmic war. To the extent that they convinced us of the validity of this worldview, they were successful.

Most people in the Muslim world rejected the premises behind that image, and refused to accept the notion of cosmic war. They thought the attack was simply an extreme act of a small group of misfits, or possibly a conspiracy conjured up by the CIA or Israeli secret agents.

Alas, among those who took the image seriously as a valid assertion that great forces were combatting on a global scale were many in the Western media and many political leaders, including the inner circle of the George W. Bush presidency. Hence the “global war on terror” theme that dominated US foreign policy for the rest of the Bush presidency and that lingers on today.

Involving the US in active military engagement was useful for the jihadi ideology since it fulfilled its proposition that the US was the major force that was combatting Muslim politics. The ensuing US invasion and occupation of two Muslim countries, Afghanistan and Iraq, were further signs that the al Qaeda prophecy of cosmic war was being fulfilled.

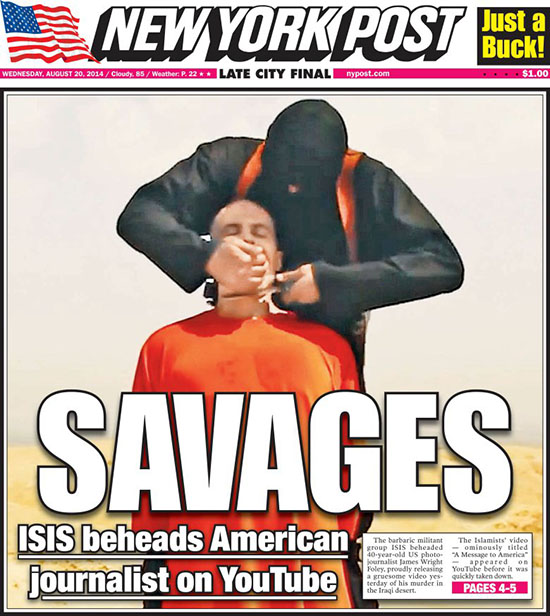

In 2004, after the invasion of Iraq, the al Qaeda strategy in Iraq itself also turned to extreme violence. In this case it was the beheadings of seemingly innocent American travelers and journalists.

These mesmerizing acts of terror had two effects. They pulled the US even deeper into military engagement with Sunni Iraqis, thereby alienating the general population of Sunni Iraqis even more than they had been. And these acts also had a chilling effect within the Sunni community —it showed that these forces meant business and were willing to take a life-and-death stance. As a result, it attracted many young Sunnis into the al Qaeda fold, especially after the US attacks and demolition of the city of Fallujah later that year.

For several years it seemed that al Qaeda in Iraq would be a permanent fixture of Sunni politics in the country. Then a remarkable thing happened. Sunni leadership became weary of the extremism, the killings, and the rigidity of al Qaeda, and were lured by a savvy project engineered by US General David Petraeus to remove US troops from the Sunni regions of Iraq and support the Sunni leadership in their efforts to rid themselves of the al Qaeda extremists. This was the so-called Awakening of 2008. Since then, al Qaeda in Iraq has stayed in the shadows.

In 2014, all that changed. After a bitter fight with al Qaeda leadership in Syria and in its central leader, Ayman al Zawahiri, one man came out on top: the Iraqi extremist leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. The Syrian and Iraqi extremist Sunni forces were united under the banner of his Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (the Levant, greater Syria) — ISIS or ISIL. In a blitzkrieg across the region it seized vast reaches of Sunni territory in Iraq the size of Pennsylvania, including the second largest city in the country, Mosul.

Then the beheadings began. In some ways the purposes were the same as they were in 2004. The beheadings of Western journalists and aid workers were clearly meant to inflame the anger of America and the West, and to draw them into a war that would be seen (the jihadis hoped) as evidence of Western militancy against Islam in general. To some extent, that strategy is working.

But there were also large numbers of beheadings of recalcitrant local Sunnis—far more than the Westerners, in fact—that were carried out in hideously public ways, their severed heads displayed on fence posts for all to see. Clearly the point of these actions were meant to intimidate the local population, and to deter any movement towards counterrevolution similar to the Awakening project that had successfully turned the modern Sunni leadership against al Qaeda in Iraq ten years ago.

And there was one more effect of these public acts of horror. In an era of the Internet where Twitter, YouTube and countless other social networks are available to instantly project the power of terrorist acts, these events were meant for a global audience. Specifically they were meant for a global audience of disaffected young Muslim men around the world.

The videos of these beheadings were recruiting devices. As shocking as it might seem to most of us, they had an odd appeal to young men who felt alienated from society and eager to join a force that was bigger than themselves, one that was tough, determined, and took no prisoners. ISIS was for them, and in recent months they have joined in the thousands, streaming from Europe, Britain, US, Australia, Russia, China, even India.

This is new. The old al Qaeda in Iraq did not show much interest in involving foreigners, who would not be well trained for military service, after all, and often would have language barriers that would make them less than ideal soldiers. Moreover they would be coming to battle eager to fight and to kill; they would be loose cannons in a carefully controlled army.

That is probably al Baghdadi’s point. The bulwark of the ISIS military force in Iraq comes from Saddam Hussein’s old army, who were denied roles in the new army in Iraq. Now they have a place, and they are old, seasoned, disciplined soldiers. They likely are not disposed to extremism in any form, and probably are suspicious of the ISIS leadership and its rigid, violent methods. They are also probably the most likely to turn against ISIS some time in the future, should an Awakening kind of solution be offered from the government in Baghdad.

In other words, the old Iraq army stalwarts in ISIS need to be held in check. The intimidating public beheadings are certainly a deterrent. An even greater deterrent is the large number of passionate foreign fighters who would be more than eager to turn against any old army superior who was deemed to be soft or less than loyal to the ISIS regime.

So extreme terror can be a useful device. Whether it will be sufficient in time remains to be seen, especially since there are efforts in Baghdad to be more open and conciliatory to Sunni interests—in other words, to launch a new Awakening that would turn Sunni leadership against their ISIS rulers. That is probably the only thing that will turn the situation around. When that happens the counterrevolutionary Sunnis will have to fight against not only Iraqi extremists but impassioned foreigners willing to die with a vengeance. By luring the foreigners with terrorist images, the ISIS leaders have created a whole new complication to any easy solution in the region.